By Will Duru, BSc (Hons) Sport and Exercise Science, Award winning Personal Trainer with over 10 years of experience in strength training

The diagnosis hits hard. A strained shoulder. A tweaked lower back. A dodgy knee. Suddenly, the training you love becomes complicated.

Most people respond to injury in one of two ways. Some stop training entirely, watching weeks of progress disappear while they wait for full recovery. Others ignore the injury completely, training through pain until a minor issue becomes a major one.

Both approaches are wrong.

The truth is that most injuries allow continued training with intelligent modifications. You can maintain fitness, preserve muscle and even continue progressing in unaffected areas while the injured part heals. Often, staying active actually accelerates recovery.

This guide provides strategies for training safely around common injuries. It is not medical advice and does not replace professional diagnosis. But it offers a framework for maintaining your training when injury strikes.

The Case for Continued Training

When injury occurs, the instinct to stop everything is understandable but often counterproductive.

Muscle loss happens quickly. Research shows measurable decreases in muscle size within just two weeks of inactivity. Complete rest for a minor injury can cost more muscle than the injury itself.

Cardiovascular fitness declines rapidly. Within three to four weeks of stopping exercise, significant deconditioning occurs. Returning after extended rest means rebuilding fitness you had already earned.

Mental health suffers. For regular exercisers, sudden removal of training negatively impacts mood, sleep and stress management. The psychological cost of complete rest is often underestimated.

Movement aids healing. Appropriate movement increases blood flow to injured tissues, supporting recovery. Complete immobilisation is rarely optimal for soft tissue injuries after the initial acute phase.

The goal is finding ways to train that do not aggravate your injury while maintaining as much fitness as possible. This requires thoughtful modification, not abandonment.

General Principles for Training Around Injury

Before discussing specific injuries, these principles apply broadly:

Principle 1: Get Proper Diagnosis

Before modifying your training, understand what you are dealing with. A pulled muscle requires different management than a torn ligament. A disc issue differs from muscular back pain.

See a physiotherapist, sports medicine doctor or other qualified professional. Self-diagnosis leads to inappropriate training modifications that can worsen injuries.

Principle 2: Pain Is Information

Mild discomfort during movement may be acceptable. Sharp pain, increasing pain or pain that persists after exercise is not. Learn to distinguish between the general discomfort of working hard and the specific pain signalling tissue damage.

If an exercise hurts the injured area, stop. Find an alternative that does not provoke pain. “No pain, no gain” does not apply to injured tissues.

Principle 3: Train What You Can

An injured shoulder does not prevent leg training. A knee injury does not stop upper body work. A back issue may still allow many exercises with modification.

Identify what remains unaffected and train it. Maintaining training stimulus to healthy tissues preserves overall fitness while injured areas recover.

Principle 4: Modify Before Eliminating

Before removing an exercise entirely, explore modifications. Reducing weight, changing range of motion, altering grip or stance, or switching to a similar but less aggravating variation often allows continued training.

Only eliminate exercises when no modification permits pain-free performance.

Principle 5: Progress Gradually Back

When returning to previously painful exercises, start conservatively. Use lighter weights than before the injury. Rebuild gradually over weeks rather than jumping back to previous levels.

Reinjury often occurs from returning too aggressively. Patience during return prevents setbacks.

Training Around Shoulder Injuries

Shoulder injuries are among the most common gym issues. The shoulder joint sacrifices stability for mobility, making it vulnerable during pressing and overhead movements.

What Usually Hurts

Rotator cuff strains, impingement and general anterior shoulder pain frequently affect lifters. Bench press, overhead press and lateral raises commonly aggravate these conditions.

Modifications to Try

Reduce pressing range of motion. Stop the bench press a few centimetres above your chest rather than touching. Use a board or pad to limit depth. This often eliminates the painful portion of the movement.

Change grip width. Wider grips increase shoulder stress for many people. Bringing hands slightly narrower may reduce pain.

Switch pressing angles. If flat bench hurts, try incline or decline. If overhead press aggravates, floor press or landmine press may be tolerable.

Use neutral grip. Palms facing each other rather than forward reduces shoulder strain. Neutral grip dumbbell presses often feel better than barbell variations.

Prioritise rowing. Many shoulder issues benefit from increased pulling volume. Rows, face pulls and reverse flyes can often continue or even increase while pressing takes a back seat.

What to Avoid

Upright rows, behind-the-neck presses and extreme ranges of motion on flyes typically aggravate shoulder issues. These movements place the shoulder in vulnerable positions under load.

What You Can Still Train

Lower body training is usually unaffected by shoulder injuries. Goblet squats, leg press, leg curls and most leg exercises remain options. Core training that does not load the shoulders continues safely.

Training Around Lower Back Injuries

Lower back issues strike fear into lifters, often leading to complete training cessation. Yet most back problems allow significant continued activity with appropriate modification.

What Usually Hurts

Muscular strains, disc irritation and general lower back pain affect many gym goers. Deadlifts, squats and bent-over rows commonly become problematic.

Modifications to Try

Reduce spinal loading. Switch from back squats to leg press, belt squat or goblet squats held at chest height. These train legs with less spinal compression.

Support your back. Seated rows with chest support, chest-supported dumbbell rows and machine rows remove the lower back from the equation while training upper body.

Change hip hinge variations. If conventional deadlifts hurt, try Romanian deadlifts with lighter weight, trap bar deadlifts with a more upright torso, or hip thrusts that reduce spinal stress.

Brace effectively. Learning proper bracing technique often allows return to exercises that previously hurt. A weak brace during lifting contributes to many back issues.

Avoid loaded flexion. Rounding the lower back under load aggravates most back problems. Maintain neutral spine position in all exercises.

What to Avoid

Heavy axial loading, especially with compromised technique, typically worsens back issues. Good mornings, heavy back squats and conventional deadlifts often need temporary removal.

What You Can Still Train

Upper body pressing and pulling usually continue unaffected. Bench press, overhead press, rows and pull ups rarely stress the lower back significantly when performed correctly. Leg exercises that avoid spinal loading remain options.

Training Around Knee Injuries

Knee pain affects lifters at all levels. The knee joint bears significant force during lower body training, making it susceptible to overuse and acute injury.

What Usually Hurts

Patellar tendinopathy, meniscus issues and general anterior knee pain commonly trouble lifters. Squats, lunges and leg extensions often become problematic.

Modifications to Try

Reduce depth. Partial range squats to parallel or above may be pain-free when full depth hurts. Box squats to a controlled depth offer consistency.

Change stance. Some knee issues improve with a wider stance, others with narrower. Toe angle adjustments also affect knee stress. Experiment to find what feels best.

Switch squat variations. If back squats hurt, try front squats or goblet squats. The more upright torso changes knee loading patterns.

Emphasise hip dominant movements. Romanian deadlifts, hip thrusts and glute bridges train the posterior chain with less knee stress than squatting movements.

Avoid full extension under load. Leg extensions that fully straighten the knee often aggravate patellar issues. Limit range of motion or eliminate the exercise.

What to Avoid

Deep lunges, jump training and high-rep leg extensions typically worsen knee problems. Sudden direction changes and impact activities increase risk.

What You Can Still Train

Upper body training continues normally. Many hip hinge movements remain options. Swimming or cycling for cardio provides training stimulus with reduced knee impact.

Training Around Elbow and Wrist Injuries

Elbow and wrist issues affect grip, pressing and pulling movements. Tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow and wrist strains commonly occur in lifters.

What Usually Hurts

Gripping heavy weights, direct tricep and bicep work, and pressing movements often provoke pain with elbow and wrist injuries.

Modifications to Try

Use straps. Lifting straps reduce grip demands for pulling movements, often allowing continued back training when gripping hurts.

Change grip type. Switch between overhand, underhand and neutral grips. Often one grip position is pain-free while others hurt.

Use thicker bars or grips. Fat grips or thick bars change wrist position and force distribution, sometimes reducing pain.

Reduce direct arm work. Bicep curls and tricep extensions directly stress the elbow. Compound movements may be tolerable when isolation work is not.

Try machines. Machine exercises with fixed paths reduce grip and stabilisation demands compared to free weights.

What to Avoid

Exercises with heavy grip demands and direct arm isolation work typically need reduction or elimination. Wrist curls and reverse curls often aggravate wrist issues.

What You Can Still Train

Lower body training is usually unaffected. Core training that does not require gripping continues safely. Pressing with modified grip may remain possible.

Sample Modified Training Week

Here is an example of how training might look while recovering from a shoulder injury:

Day 1: Lower Body

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leg Press | 4 | 10 | No shoulder involvement |

| Romanian Deadlift | 3 | 10 | Light grip, straps if needed |

| Leg Curl | 3 | 12 | Unaffected |

| Calf Raises | 3 | 15 | Unaffected |

| Plank | 3 | 30 sec | No shoulder loading |

Day 2: Upper Body (Modified)

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Grip DB Press | 3 | 10 | If pain-free, limited range |

| Chest Supported Row | 4 | 10 | Increased rowing focus |

| Face Pulls | 3 | 15 | Rehab and strengthening |

| Lat Pulldown | 3 | 10 | Usually tolerable |

| Cable Curl | 2 | 12 | If grip allows |

Day 3: Lower Body

| Exercise | Sets | Reps | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goblet Squat | 4 | 10 | Held at chest, less shoulder |

| Hip Thrust | 3 | 12 | No shoulder involvement |

| Walking Lunges | 3 | 10 each | Arms at sides |

| Leg Extension | 2 | 15 | Unaffected |

| Dead Bug | 3 | 8 each | Core without shoulder load |

This structure maintains three training days, preserves lower body work completely, allows modified upper body training and includes exercises that support shoulder recovery.

When to Stop Completely

Some situations require complete rest from affected areas:

Acute injury phase. The first 48 to 72 hours after acute injury typically require rest, ice and reduced activity. Do not push through fresh injuries.

Increasing pain. If modified training causes pain to worsen rather than stay stable, further modification or rest is needed.

Medical instruction. If a healthcare professional advises against training, follow their guidance. They have information about your specific situation that general advice cannot address.

Post-surgical recovery. Surgery requires specific rehabilitation protocols. Do not improvise modifications after operations.

Even in these situations, unaffected body parts may still be trainable. Complete whole-body rest is rarely necessary for single-joint injuries.

The Mental Side of Injury

Injury challenges more than your body. The frustration of modified training, the fear of losing progress and the uncertainty of recovery all affect mental state.

Accept temporary limitations. Fighting against reality increases frustration. Accepting that training will look different for a while allows focus on what remains possible.

Celebrate what you can do. Rather than mourning lost exercises, appreciate continued training capacity. Many people cannot train at all. Modified training is still training.

Use the time productively. Injury often reveals weaknesses. A shoulder injury might expose neglected back development. A knee issue might highlight hip weakness. Address these gaps during recovery.

Trust the process. Most gym injuries heal with time and appropriate management. The setback is temporary. Consistent modified training maintains more fitness than complete rest.

A Client Who Came Back Stronger

Sarah developed tennis elbow that made gripping painful. Her initial reaction was to stop all upper body training entirely.

Instead, we modified her programme. We used straps for all pulling movements. We switched to machines that reduced grip demands. We temporarily eliminated direct bicep work while increasing tricep and shoulder training that did not aggravate the elbow.

Her lower body training continued unchanged. Her legs actually improved during this period because she could focus energy there without upper body fatigue.

After eight weeks, her elbow had healed. She returned to normal training with grip strength slightly reduced but everything else intact. Her squat had actually increased during the injury period.

“I expected to lose everything,” she said. “Instead, I just trained differently for a while and came out the other side without missing much.”

Smart modification beats complete rest almost every time.

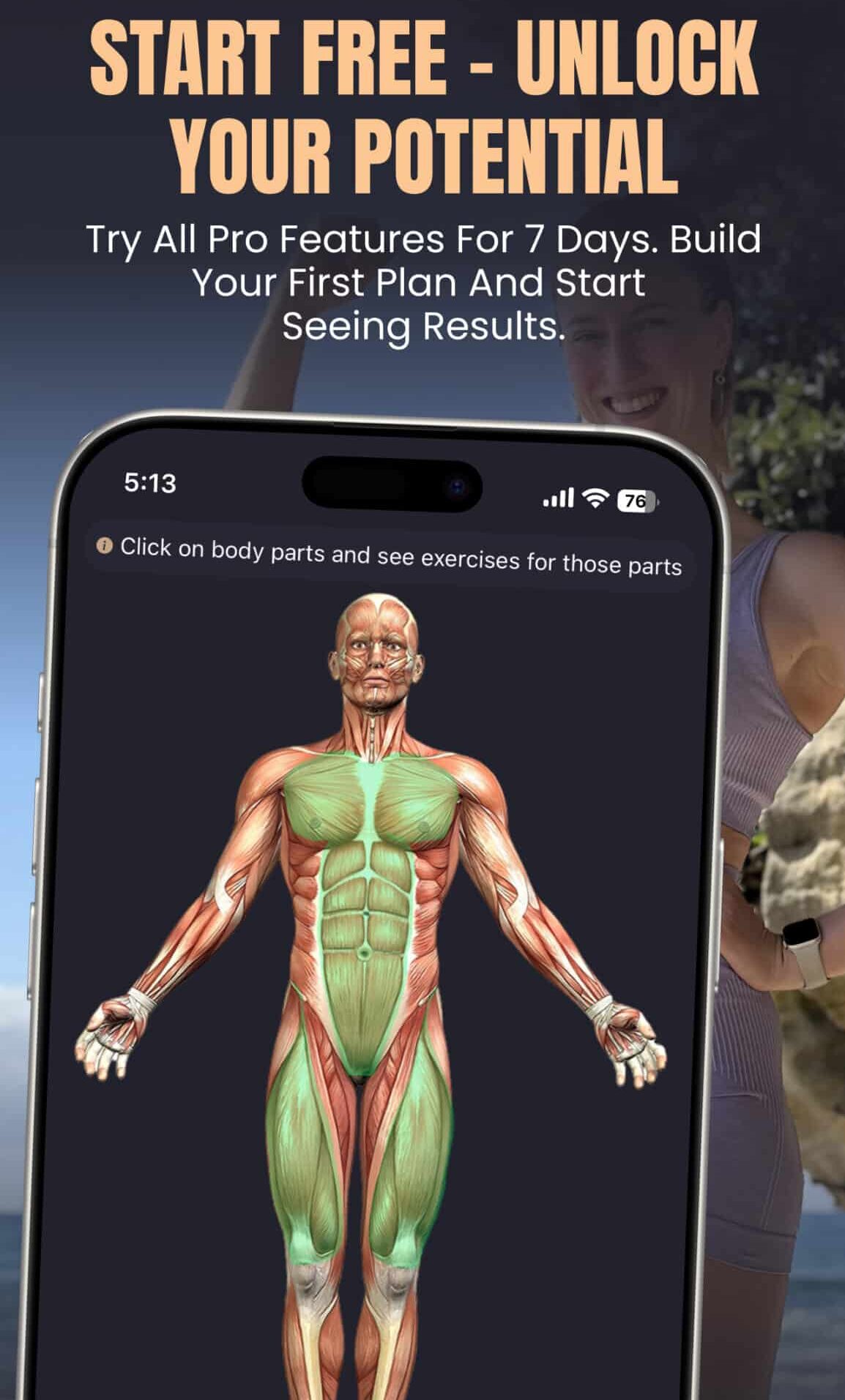

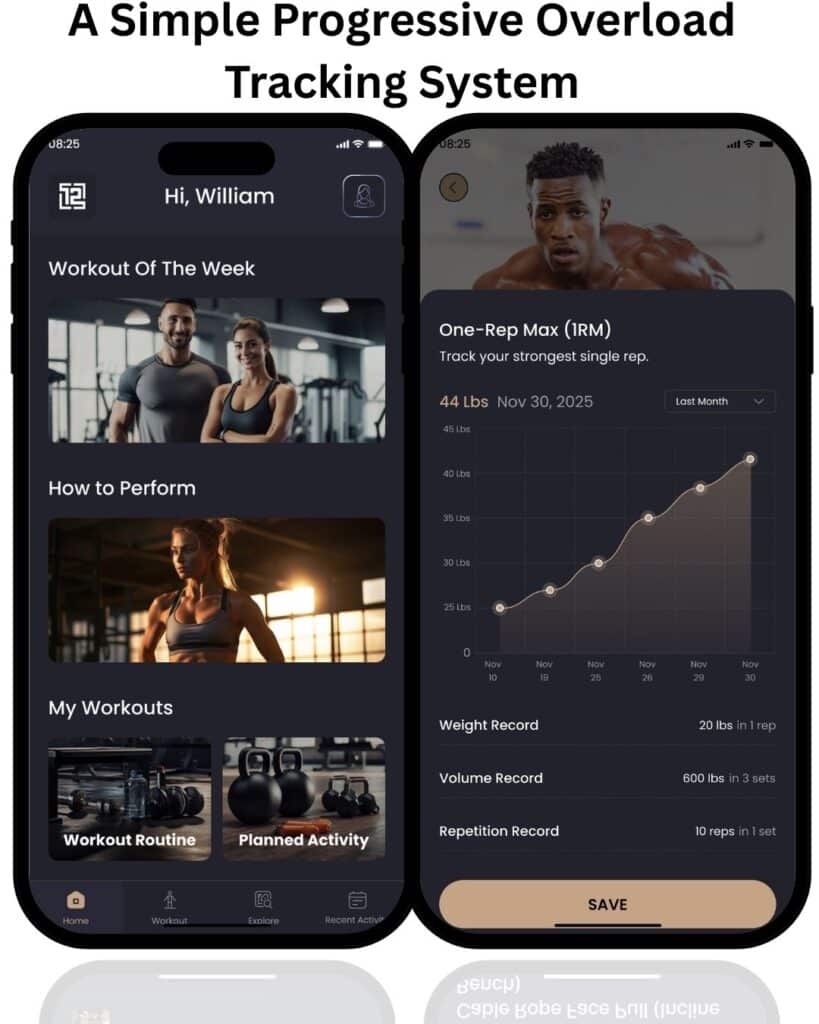

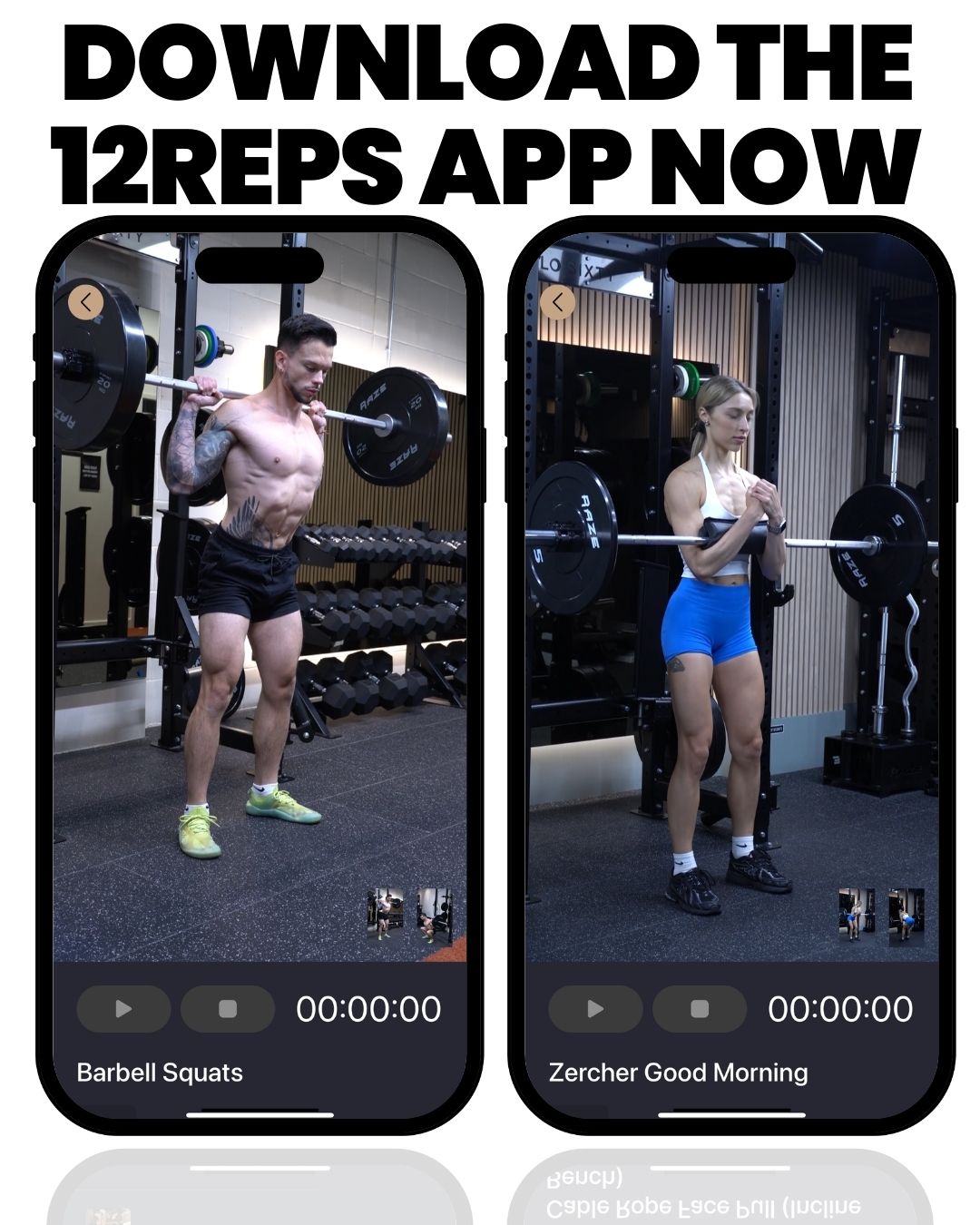

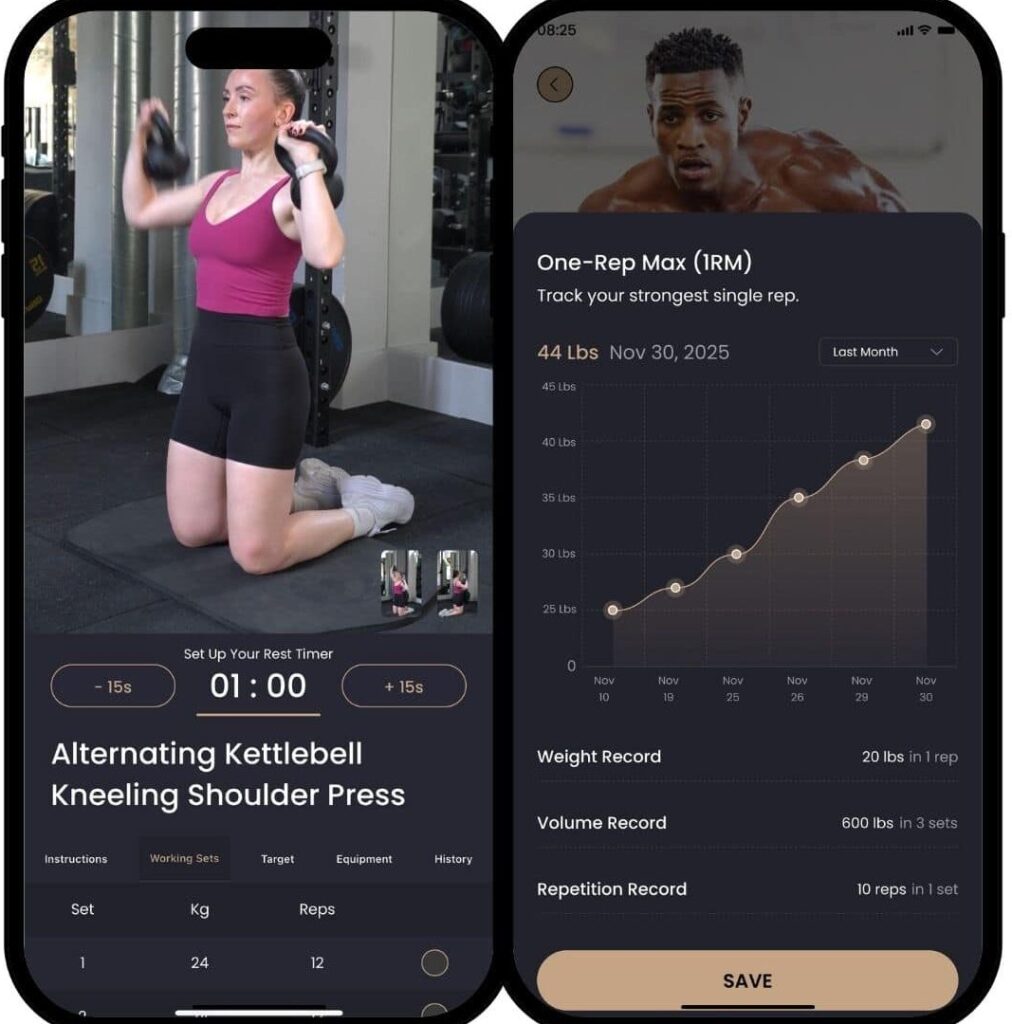

Working with the 12REPS App During Injury

The 12REPS app allows you to modify programmes based on available equipment and physical limitations. You can swap exercises, adjust workouts to avoid problematic movements and track progress on the exercises you can perform.

12REPS APP has exercise breakdown videos that teach all the cues and do’s and don’ts to help you avoid injury.

This flexibility helps maintain structured training even when injury requires significant modification. You continue following a programme rather than improvising random workouts.

Conclusion

Injury does not have to mean lost progress. With proper diagnosis, intelligent modification and patience, most injuries allow continued training in some form.

Train what you can. Modify before eliminating. Respect pain signals. Progress gradually back to full training as recovery allows.

The time away from certain exercises is temporary. The fitness maintained through modified training makes return easier and faster. Stay active, stay smart, and trust that you will come back.

Related Articles on just12reps.com

| Article | Description | Link |

|---|---|---|

| How to Warm Up Before Lifting | Proper preparation reduces injury risk. | Read Article |

| Complete Beginner’s Guide to Strength Training | Build a foundation with proper technique from the start. | Read Article |

| Why You’re Not Seeing Results | Ensure your training approach is not causing problems. | Read Article |

| Progressive Overload Guide | Return to progression safely after injury recovery. | Read Article |

| How to Build a Gym Habit | Maintain consistency even during modified training periods. | Read Article |

References

[1] Fisher, J. et al. (2011). Prescribed and self-selected rest periods in resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/pages/default.aspx

[2] Glasgow, P. et al. (2015). Optimal loading: key variables and mechanisms. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://bjsm.bmj.com/

[3] Khan, K.M. & Scott, A. (2009). Mechanotherapy: how physical therapists’ prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://bjsm.bmj.com/

[4] Wall, B.T. et al. (2013). Substantial skeletal muscle loss occurs during only 5 days of disuse. Acta Physiologica. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/17481716

[5] Bleakley, C.M. et al. (2012). PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE? British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://bjsm.bmj.com/

About the Author: Will Duru holds a BSc (Hons) in Sport and Exercise Science and is an award winning personal trainer with over 10 years of experience helping clients train safely and effectively through all circumstances. He is the creator of the 12REPS app, designed to provide flexible training guidance that adapts to individual needs.