By Will Duru, BSc (Hons) Sport and Exercise Science, Award-winning Personal Trainer with over 10 years of experience in strength training and optimising recovery

Training intensity is more than just the weight on the bar, or the number of reps performed. Two advanced tools, Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) and Reps in Reserve (RIR), help lifters gauge workout intensity more precisely.

These metrics enable autoregulatory training, adjusting effort based on how you feel each day, so you’re not constantly pushing to failure (which can lead to excess fatigue) or coasting too easily.

In this article, we’ll compare RPE and RIR, explain when to use each, and demonstrate how the 12-rep workout app integrates these metrics for more effective workout intensity tracking. By the end, you’ll know which metric fits your needs and how 12reps can help you train with optimal intensity for better results.

Understanding Workout Intensity: Beyond Just Weight

Lifting heavier weights or doing more reps isn’t the only way to measure intensity. Training to absolute failure every set isn’t always optimal. While going to failure can recruit more muscle fibers, it also dramatically increases fatigue and recovery time.

In fact, research from the National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM) warns that consistently training at RPE 10 (or RIR 0 – true failure) may compromise strength gains due to overtraining.

Leaving even a couple of reps “in the tank” (stopping short of failure) can improve recovery and maintain performance in subsequent sessions. This is where autoregulation comes in – adjusting intensity based on your body’s feedback.

Autoregulation means listening to your daily condition and adjusting the load or reps accordingly. Factors such as sleep, nutrition, and stress can impact your strength on any given day. Traditional percentage-based training doesn’t account for these day-to-day fluctuations.

By using RPE or RIR as intensity metrics, you can adjust your effort in real-time, pushing harder on strong days or easing up on days when you feel fatigued. This helps prevent overtraining or undertraining, keeping you in the optimal intensity zone for progress. Autoregulation can complement your overall periodisation plan by fine-tuning each workout to your current capability.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Explained

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is a subjective scale ranging from 1 to 10 that measures the perceived intensity of an exercise. An RPE of 1 means effortless (barely any effort), while an RPE of 10 means maximal effort – you couldn’t do any more reps or add weight.

The RPE concept originated from Gunnar Borg’s work in aerobic exercise (Borg’s original scale ranged from 6 to 20), but it has been adapted into a 0–10 or 1–10 scale for weightlifting.

In strength training, lifters rate each set after completion based on its perceived difficulty. For example, if you perform a set of squats and feel you could have done two more reps before failure, you’d rate it about RPE 8 (since it was hard but not maximal).

Benefits of RPE: RPE is simple and intuitive – you only need to judge your overall effort. This makes it a good starting point for beginners to gauge intensity without overcomplicating things. RPE also automatically accounts for daily performance variability.

If you’re tired or under-recovered, a weight that usually feels like RPE 6 might feel like RPE 8 on that day, signalling you to adjust your load or reps. In this way, RPE puts all individuals on a level playing field by personalising intensity relative to your capacity.

Studies have validated RPE as a reliable method for estimating exercise intensity and monitoring training stress. It’s beneficial for tracking how you feel across workouts – helping you avoid pushing too hard when your body needs a break, or identifying when you can safely increase intensity.

Limitations of RPE: Because RPE is subjective, it relies on honest self-assessment. Lifters (especially novices) may struggle to rate themselves accurately. In fact, research has shown that even when bodybuilders reached failure, they often reported RPE scores below 10 (i.e., they didn’t label it maximal).

This means some people subconsciously “save” the 10/10 rating for an almost impossible effort. Meanwhile, those lifters were actually quite good at estimating their reps in reserve (as we’ll see with RIR). In short, RPE can be somewhat inconsistent between individuals – one person’s RPE 8 might be another’s RPE 6 in terms of the actual weight lifted. With experience and video feedback, lifters can calibrate their RPE ratings over time.

But early on, it helps to use RPE alongside objective cues (like bar speed or heart rate) to ensure your perceived exertion matches reality. Remember that RPE is measured after completing the set – don’t try to decide mid-set, just focus on the exercise, then reflect on how hard it was.

How to gauge RPE: After a set, ask yourself, “How hard was that on a scale of 1 to 10?” A more precise way to think is to consider RIR first: if you believe you had about 2 reps left in the tank, that equates to roughly RPE 8.

Could you barely finish the set with no reps left? That’s RPE 10 (max effort). Could you have done 4–5 more reps? That’s around RPE 6 (pretty easy). By mentally converting to “reps left,” you can assign an RPE number more objectively.

Reps in Reserve (RIR) Explained

Reps in Reserve (RIR) represents how many more repetitions you could have done in a set before reaching failure. Instead of rating your effort on a numeric scale, you literally estimate the number of reps left “in the tank.” For example, if you stop a bench press set at 8 reps and feel you could do 2 more if necessary, that set is recorded as RIR 2.

An RIR of 0 means you have reached failure (no reps left; you have given everything). RIR is essentially an alternate view of intensity – it directly measures proximity to failure, whereas RPE measures perceived difficulty. In practice, RIR and RPE are closely linked: RIR 2 corresponds to approximately RPE 8, RIR 1 to RPE 9, and RIR 0 to RPE 10. Many strength coaches use an RIR-based RPE scale, where each RPE value corresponds to a specific RIR (see the table below).

Benefits of RIR: RIR tends to feel more concrete for experienced lifters because it’s tied to performance. It forces you to consider your actual capacity (“I could have done 1 more rep” is easier to grasp than “that was 9 out of 10 effort”). Research indicates that an RIR-based approach can more accurately gauge intensity for near-limit sets than traditional RPE ratings. In other words, when lifting heavy or approaching failure, counting your reps in reserve may reflect true effort better than a generic RPE number. Hackett et al.

(2012) found that trained bodybuilders could accurately predict their remaining reps, and their estimates improved as they accumulated fatigue across sets. This suggests RIR is a skill that improves with practice. Another advantage is that RIR has a direct link to training goals – if a program calls for “leave 2 reps in reserve,” it is explicitly telling you how hard to push.

This helps in programming for strength or hypertrophy, where you often want to be near failure but not at failure for optimal results. RIR also shares the flexibility of RPE in adjusting for daily fluctuations: if you’re weaker one day, you’ll reach your target RIR with fewer reps or lighter weight, and vice versa, ensuring the relative intensity stays consistent.

Limitations of RIR: Estimating RIR requires some experience and body awareness. Beginners may find it challenging to determine how many more reps they truly have left because they haven’t yet tested their limits. In fact, studies show that the ability to gauge RIR (like RPE) is more reliable in experienced lifters than novices.

A novice might think they have 0 RIR (cannot do more) when, in fact, they could do several more reps with encouragement. Thus, if you’re new to RIR, treat it as a learning tool: you might occasionally take a set to actual failure to check if your RIR estimates are accurate. Another limitation is that RIR is most useful in a moderate rep range. It’s uncommon to use RIR values above 4 or 5, because being that far from failure is both difficult to estimate and usually not productive for strength gains.

For example, whether a set is 8 RIR or 10 RIR (very light) isn’t very meaningful – at that point, you’re just doing a warm-up. So RIR is primarily used for working sets that are within a few reps of failure (RIR 0–3). Finally, like RPE, RIR relies on honesty and consistency. Some days, you might stop short and call it RIR 2 when you had more in you. With time, watching bar speed and your form can help refine your RIR judgments (slow, grinding reps at the end typically indicate you’re truly near your limit).

How to gauge RIR: During the last rep or two of your set, assess how many more good reps you could do. If you think, “I might manage one more rep, but it would be a grind,” that’s RIR 1. If you could easily do a couple more, maybe it’s RIR 3.

You usually log RIR immediately after the set (you can even jot it down in the 12reps app’s logger). It may help to test yourself occasionally: if you record RIR 2, you could later attempt those extra reps carefully to see if you indeed had two left. This feedback loop will improve your accuracy.

RPE vs. RIR: Which One is Right for You?

Now that we’ve defined RPE and RIR, you might be wondering if one is “better.” The truth is, RPE and RIR are closely related and often interchangeable – they are like two sides of the same coin. In fact, prescribing “RPE 8” vs “RIR 2” is almost redundant because an RPE 8 effort typically means about 2 reps in reserve. Both metrics serve to regulate intensity and prevent you from overreaching or slacking off. However, there are scenarios where one might be more convenient than the other:

Ease of Use: For many lifters, especially beginners, RPE is simpler – you just give a 1–10 rating of how hard it felt. It doesn’t require knowing exactly how many reps you could have done. New lifters may not recognise their proper limits, so RPE allows a broad estimation. (That said, beginners often perceive everything as difficult at first and may overestimate their RPE.

If you’re new, it’s okay to stick to moderate RPE 5–6 efforts initially to learn your capacity.) RIR, on the other hand, might suit experienced lifters who are comfortable assessing their limits. If you’ve been training for years, you can often tell closely whether you had 1, 2, or 3 reps left. This makes RIR a powerful tool for advanced programming – for example, a powerlifter might plan heavy triples at 2 RIR to maximise strength without hitting failure.

Type of Exercise: Some exercises lend themselves to one scale or the other. Higher-rep sets or endurance-based exercises (like a 20-rep squat, or a timed plank hold, or accessory moves like bicep curls) can be tricky to count RIR because the fatigue is more gradual and the rep count is high.

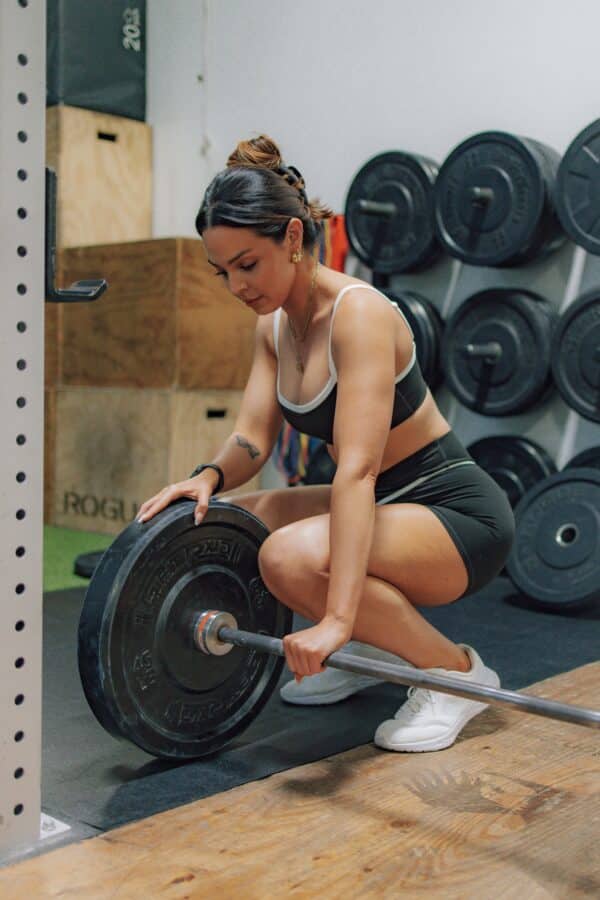

In these cases, using RPE is often more practical – you can simply rate the set as, say, 8/10 hard, without needing an exact rep count. RPE is also functional for isolation exercises and cardio or circuit training. In contrast, big compound lifts and lower-rep sets are great for applying RIR. On exercises like the squat, deadlift, or bench press (especially when done early in a session when you’re fresh), lifters often prefer RIR to guide their intensity.

For example, you might plan to deadlift 5 sets of 5 at “2 RIR,” adjusting the weight so that you always leave two reps in the tank each set. Research supports the use of RIR for these primary lifts. In the earlier-mentioned study, lifters under heavy load could accurately gauge their RIR, even when they struggled to provide a clear RPE rating.

Personality and Preference: Some individuals prefer one metric over another. If you find numbers comforting and like the idea of “I stopped with one rep left,” then RIR might click with you. If you prefer a more qualitative feeling (“that set felt like a 9/10 effort”), RPE might be your go-to.

You can even use both: for example, log an RPE for how the set felt, and note the RIR to cross-check. Over time, you’ll see they correlate. In fact, many programs define one in terms of the other (e.g., “Squat – 3 sets of 8 at RPE 8 (~2 RIR)”). It’s not an either/or choice so much as what helps you execute the workout as intended.

To sum up the comparison, here’s a quick reference:

Metric | Scale | Indicates | Best For | Potential Drawbacks |

RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) | 1–10 (subjective effort rating) | How hard the set felt overall (10 = max effort, 1 = very easy) | Beginners, high-rep or endurance sets, overall session intensity tracking | Subjective; novices may misrate; some avoid using 10 even at failure. |

RIR (Reps in Reserve) | 0–? (count of reps left) | How many more reps could you have done (0 = at failure) | Experienced lifters, heavy compound lifts, precise load adjustment | Challenging for novices to gauge; not useful for very light sets; still relies on honest self-assessment. |

Both methods aim to keep you in an optimal intensity range (often around RPE 7–9 or RIR 1–3 for work sets) to stimulate progress without burning out. For a typical healthy lifter, training mainly in the RPE 7–8.5 (RIR 1–3) range is effective and safe.

Occasionally hitting RPE 9–10 (0 RIR) is fine – even beneficial for pushing limits – but doing so too often can hinder recovery. Conversely, consistently logging very low RPEs (e.g., RPE 4–5 with lots of RIR) means you’re likely under-training and could bump up the weights. By understanding both scales, you can choose the one that helps you train with the right effort.

Some days, you might favour RPE (“Today I feel about a 7, I’ll stop there”), while other days, you might favour RIR (“I have two reps left, so I’m on target”). Both roads lead to Rome if you are using them to regulate intensity intelligently.

Training with Precision: How 12reps Integrates RPE & RIR

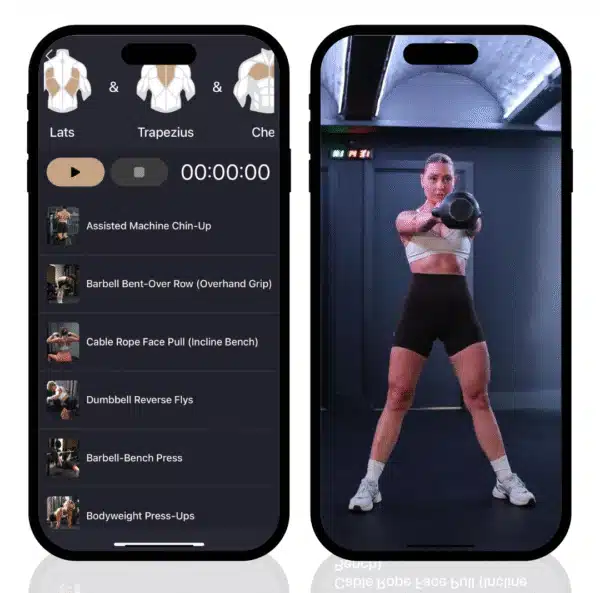

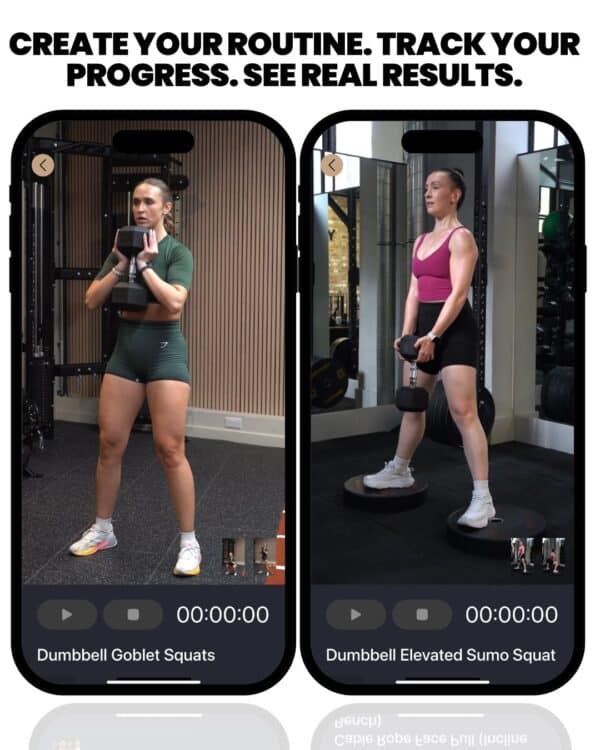

Modern workout apps like 12reps have recognised the power of RPE and RIR for tracking workout intensity. The 12-reps app allows you to log either RPE or RIR for each set of your exercise, giving you a convenient way to record how hard you worked beyond just the weight and reps. This turns subjective effort into trackable data.

How does this help you? First, by logging RPE/RIR consistently, you’ll gather a history of your training intensity. The app’s powerful filtering algorithm utilises this data to identify patterns and provide informed suggestions. Unlike generic “AI” coaches that can be a black box, 12reps employs a transparent algorithm to filter and tailor workout recommendations based on your actual performance.

For example, say your program calls for 3 sets of 10 reps on the bench press at RPE 8. In the 12-rep app, you perform your sets and log RPEs of 8, 8.5, and 9 for the three sets (as you fatigue, the RPE increases). The app records not only the weights and reps, but also how close you were to failure.

Next time you bench, 12 reps could remind you of the intensity from your last session – if you logged a higher RPE than planned (meaning it was tougher than expected), the app might suggest using a slightly lighter weight or sticking with the same weight until your RPE comes down to your target. If you logged a lower RPE (easier than expected), 12reps will flag that you had more in the tank and could increase the weight or reps.

This ensures progressive overload while keeping you within a safe effort range. Over time, as you input RPE/RIR, 12reps can even estimate changes in your one-rep max (1RM) and strength levels – e.g., if a weight that used to be RPE 9 is now RPE 7, your strength has improved.

The app’s algorithm sifts through your log data to give you actionable insights, such as: “Your squat sets have been consistently at RPE 9–10 for the last two weeks – consider a deload or lighter session to recover,” or “Last overhead press session was RPE 6 – you can afford to increase the weight this week.” These kinds of intelligent prompts help you avoid overtraining (too many maximal-effort days) and undertraining (never pushing hard enough).

Using 12reps, you can also filter your past workouts by RPE or RIR. Want to see all the sets where you hit RPE 10 (failure) in the last month? A quick filter shows you those peak efforts – maybe you’re hitting failure too often on deadlifts, for instance.

Or filter to see all the times you rated an exercise below RPE 6 – indicating it might be time to increase the challenge. This data-driven approach, powered by 12reps’ algorithm, eliminates the guesswork from adjusting your training. It’s like having a logbook that talks back to you with guidance.

The 12reps app doesn’t rely on magic or AI; instead, it uses your inputs and a smart filtering system to personalise you’re training. It supports both those who prefer RPE and those who prefer RIR – you can choose your metric in the app’s settings for each exercise. Logging is simple: after a set, enter a number for RPE or RIR alongside the weight and reps.

The app takes care of the rest, crunching the numbers and displaying the trends. You’ll get to visually see if you’re usually training at the intended intensity. For instance, your workout summary might show an average RPE per session, or how your RIR on squats has decreased over weeks as you push closer to a peak attempt. This not only keeps you honest with yourself but also helps you communicate with coaches or training partners about how you’re handling the program.

Perhaps one of the best features is how 12reps uses RPE/RIR to inform future workouts. Many top coaches plan workouts with target RPEs – e.g., “work up to a set of 5 at RPE 8.” The 12reps app can assist here by providing an RPE calculator or guidance based on your history.

If you have a target RPE in your next workout, 12 reps can help estimate the weight that might correspond to it, using your past logs (like how some apps have an RPE-based weight calculator). This means when you head into the gym, you’re not guessing blindly – the app might say, “Last week you did 100 kg for 5 reps at RPE 8.5, so for an RPE 8 target, try 97.5 kg for 5 reps.” This level of precision enables you to progress steadily without overshooting.

Beyond the numbers, using RPE and RIR with 12reps encourages a mindful approach to training. As you log how each set felt, you become more in tune with your body’s signals. Over weeks and months, you’ll gain a deep understanding of your personal capacity on each exercise, and you’ll appreciate how much smart training can accomplish. The app acts as a coach in your pocket, reminding you to train with intent: sometimes to push harder, sometimes to back off.

Internal Links: The 12reps app also offers plenty of resources to maximise your training. Be sure to explore the app’s workout logging features to see how you can record notes, track rest times, and more alongside RPE/RIR. And if you’re interested in long-term planning, check out our article on periodization to understand how RPE and RIR fit into bigger training cycles.

Conclusion: Mastering RPE and RIR can take your training to the next level. These metrics empower you to adjust intensity on the fly, ensuring you get the most out of each workout without burning out. Whether you prefer the simplicity of RPE or the precision of RIR (or use both), the key is consistency and honesty in your ratings.

The 12-reps app makes this process easier by providing a dedicated platform to log and analyse your RPE/RIR data. By training with this level of precision, you’ll experience better recovery, more consistent gains, and a deeper understanding of your own performance.

Ready to train smarter and see real results? Take control of your workout intensity with 12reps. Track your RPE and RIR, listen to your body’s feedback, and watch your progress soar. Download the 12Reps app here and start your journey toward smarter, data-driven workouts today!