Written by Will Duru, BSc (Hons) Sport and Exercise Science, award-winning Personal Trainer with over 10 years of experience in strength training and optimising recovery .

As an award-winning strength and conditioning coach with over a decade of experience working with elite athletes and a background in sport science, I’ve witnessed countless runners transform their performance through strategic strength training. My name is Will Duru, and throughout my career, I’ve developed comprehensive athlete strength training programs that have helped marathon runners, Hyrox competitors, and recreational athletes alike achieve their performance goals whilst staying injury-free

The relationship between strength training and running performance is no longer a matter of debate, it’s a scientific fact. Research consistently demonstrates that runners who incorporate systematic strength training into their routine experience improved running economy, enhanced power output, and significantly reduced injury rates [1]. Yet many runners still approach strength training as an afterthought, viewing it as supplementary rather than essential to their performance development.

This comprehensive 12-week push/pull/legs program represents a fundamental shift in how we approach marathon strength training. Rather than treating strength work as separate from running, this program integrates functional movement patterns that directly translate to improved running performance. Whether you’re preparing for your first 5K, training for a marathon, or aspiring to compete in Hyrox training competitions, this program provides the foundation for athletic excellence.

Why Strength Training is the Mother of Performance

In the hierarchy of athletic development, strength sits at the foundation of all other physical qualities. This principle, often referred to as “strength as the mother of performance,” forms the cornerstone of effective athletic strength training programs. For runners, this concept is particularly crucial because the demands of distance running require not just cardiovascular fitness, but the structural integrity and neuromuscular efficiency that only comes from systematic strength development.

The science behind this principle is compelling. When we examine running biomechanics, each foot strike generates forces equivalent to 2.5-3 times body weight [2]. Throughout a marathon, this translates to thousands of repetitions under significant load. Without adequate strength to absorb and redirect these forces efficiently, runners experience energy leaks, compensatory movement patterns, and ultimately, performance plateaus or injuries.

Weightlifting for runners addresses these challenges through multiple mechanisms. Firstly, strength training improves running economy, the oxygen cost of running at a given pace, by enhancing neuromuscular coordination and reducing the energy cost of each stride [3]. Studies have shown that runners who incorporate strength training can improve their running economy by 2-8%, which translates to significant performance gains over distance [4].

The neuromuscular adaptations from strength training are particularly relevant for distance runners. Traditional endurance training primarily develops slow-twitch muscle fibres, but running performance, especially in competitive situations, requires the ability to recruit fast-twitch fibres for surges, hill climbs, and finishing kicks. Muscle building for runners through resistance training enhances the recruitment and coordination of these fast-twitch fibres, providing the power reserve that separates competitive athletes from recreational runners.

Beyond performance enhancement, strength training serves as the primary injury prevention strategy for runners. The repetitive nature of running creates predictable patterns of weakness and imbalance, particularly in the hips, glutes, and core musculature. A well-designed athlete weightlifting program addresses these vulnerabilities by strengthening the kinetic chain and improving movement quality. Research indicates that runners who engage in regular strength training experience injury rates 50% lower than those who rely solely on running for fitness [5].

The metabolic benefits of strength training for runners extend beyond the training session itself. Muscle building for runnersincreases lean body mass, which elevates resting metabolic rate and improves body composition. This is particularly beneficial for runners seeking weight loss, as increased muscle mass creates a more efficient fat-burning engine even during easy runs and recovery periods.

Understanding Energy Systems for Runners

To maximise the effectiveness of any hybrid athlete training program, it’s essential to understand how the body’s energy systems contribute to running performance. The human body operates through three distinct energy systems: the phosphocreatine system (anaerobic alactic), the glycolytic system (anaerobic lactic), and the oxidative system (aerobic). Each system plays a crucial role in different aspects of running performance, and this 12-week program strategically targets all three to create well-rounded athletic development.

The anaerobic energy systems are often overlooked in traditional distance running programs, yet they’re critical for competitive performance. The phosphocreatine system provides immediate energy for high-intensity efforts lasting up to 10 seconds. For runners, this system powers the explosive starts, sudden accelerations, and powerful hill climbs that can determine race outcomes. The glycolytic system takes over for efforts lasting 10 seconds to 2 minutes, providing the energy for sustained surges, tempo efforts, and the anaerobic contributions during threshold running.

The strength training protocols in this program specifically target anaerobic development through several mechanisms. The rep ranges of 12-15 repetitions with 45-second rest periods create a training stimulus that challenges the glycolytic system whilst building muscular endurance. This approach develops what exercise physiologists term “strength endurance”—the ability to maintain force production under fatigue, which directly translates to maintaining running form and power output during the latter stages of races.

The progression from bodyweight exercises to loaded movements mirrors the energy system development that occurs throughout the program. Phase 1 focuses on building the neuromuscular foundations and movement quality that support higher-intensity training. Phase 2 introduces external loading that challenges the anaerobic systems whilst building structural strength. Phase 3 incorporates explosive movements and heavier loads that develop anaerobic power and the ability to recruit fast-twitch muscle fibres rapidly.

This systematic approach to energy system development is particularly relevant for marathon strength training for women, as research indicates that female athletes often have greater potential for strength gains and may benefit more from anaerobic development than their male counterparts [7]. The program’s emphasis on functional movement patterns and progressive loading provides a safe and effective pathway for developing these energy systems regardless of training background.

The integration of different energy systems within each training session reflects the demands of real-world running performance. Rarely does running rely on a single energy system in isolation. Even during steady-state running, the anaerobic systems contribute to maintaining pace, particularly as fatigue accumulates. By training these systems together through circuit-style strength training, runners develop the metabolic flexibility that characterises elite performance.

Understanding these energy systems also helps explain why traditional steady-state running alone is insufficient for optimal performance development. While aerobic development remains crucial for distance running, the anaerobic contributions become increasingly important as race distances decrease and competitive intensity increases. This program ensures that runners develop all energy systems systematically, creating the physiological foundation for peak performance across a range of distances and competitive formats.

The 12-Week Push/Pull/Legs Program Overview

This comprehensive athlete weightlifting program is structured around the proven push/pull/legs split, adapted specifically for the needs of distance runners. The program divides training into three distinct workout types: push movements (chest, shoulders, triceps), pull movements (back, biceps, rear delts), and leg movements (quads, glutes, hamstrings, calves). This division allows for optimal recovery between sessions whilst ensuring balanced development across all major muscle groups.

The program spans 12 weeks divided into three 4-week phases, each with specific objectives and progressions. This periodised approach ensures continuous adaptation whilst preventing plateaus and overuse injuries. The beauty of this system lies in its simplicity and effectiveness, three workouts per week, using only free weights and bodyweight exercises, with each session lasting 45-60 minutes.

Equipment requirements are minimal, making this program accessible to runners regardless of their training environment. You’ll need access to dumbbells (or adjustable weights), a pull-up bar or resistance bands for pulling movements, and a stable surface for bodyweight exercises. This setup can be achieved in most home environments or basic gym facilities, eliminating barriers to consistent training.

The training frequency of three sessions per week allows for optimal integration with running training. The program is designed to complement rather than compete with your running schedule, with strategic placement of leg sessions to minimise interference with key running workouts. This approach recognises that for runners, strength training serves as a support system for running performance rather than the primary training focus.

Each workout follows a consistent structure: a movement-specific warm-up set followed by 4 working sets of 12-15 repetitions with 45-second rest periods. This protocol targets the strength-endurance qualities most relevant to distance running whilst providing sufficient volume for adaptation. The rep range and rest periods specifically challenge the glycolytic energy system, developing the anaerobic capacity that complements aerobic training.

Phase 1: Foundation (Weeks 1-4) - Bodyweight and Mobility Focus

The foundation phase establishes the movement patterns and neuromuscular coordination that underpin all subsequent training. This phase prioritises bodyweight exercises and mobility work, ensuring that runners develop proper movement mechanics before progressing to loaded exercises. The emphasis on bodyweight training serves multiple purposes: it allows for high training frequency without excessive fatigue, develops relative strength, and provides a safe introduction to strength training for runners new to resistance exercise.

During this phase, the primary adaptations are neurological rather than structural. The nervous system learns to coordinate complex movement patterns whilst developing the stability and control necessary for more advanced exercises. This neurological adaptation phase is crucial for runners, as many distance athletes have developed movement compensations and imbalances that must be addressed before progressing to heavier loads.

The mobility component of Phase 1 addresses the common restrictions that limit running performance and increase injury risk. Hip flexor tightness, thoracic spine immobility, and ankle stiffness are systematically addressed through dynamic warm-ups and targeted exercises. This mobility work isn’t separate from strength development, it’s integrated into the training sessions to ensure that strength gains occur through full ranges of motion.

Phase 1 Workout Tables

Push Day – Phase 1

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Push-ups (knee or full) | 1 x 8 | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Progress from knee to full to elevated feet |

Pike Push-ups | 1 x 6 | 4 x 8-12 | 8-12 | 45s | Focus on shoulder strength |

Tricep Dips (chair/bench) | 1 x 8 | 4 x 10-15 | 10-15 | 45s | Elevate feet for progression |

Plank to Push-up | 1 x 5 | 3 x 8-12 | 8-12 | 45s | Builds core and push strength |

Wall Handstand Hold | 1 x 10s | 4 x 15-30s | 15-30s | 45s | Build shoulder stability |

Pull Day – Phase 1

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Inverted Rows (table/bar) | 1 x 8 | 4 x 10-15 | 10-15 | 45s | Adjust body angle for difficulty |

Pull-ups/Chin-ups (assisted) | 1 x 5 | 4 x 5-12 | 5-12 | 45s | Use resistance band if needed |

Superman | 1 x 10 | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Focus on lower back strength |

Reverse Fly (lying) | 1 x 10 | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Bodyweight rear delt work |

Dead Hang | 1 x 10s | 4 x 20-45s | 20-45s | 45s | Build grip strength |

Legs Day – Phase 1

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Bodyweight Squats | 1 x 10 | 4 x 15-20 | 15-20 | 45s | Focus on depth and control |

Single-leg Glute Bridges | 1 x 8 each | 4 x 12-15 each | 12-15 | 45s | Progress to single leg |

Lunges (alternating) | 1 x 6 each | 4 x 12-15 each | 12-15 | 45s | Add jump for power |

Calf Raises | 1 x 12 | 4 x 15-20 | 15-20 | 45s | Single leg progression |

Wall Sit | 1 x 20s | 4 x 30-60s | 30-60s | 45s | Increase time weekly |

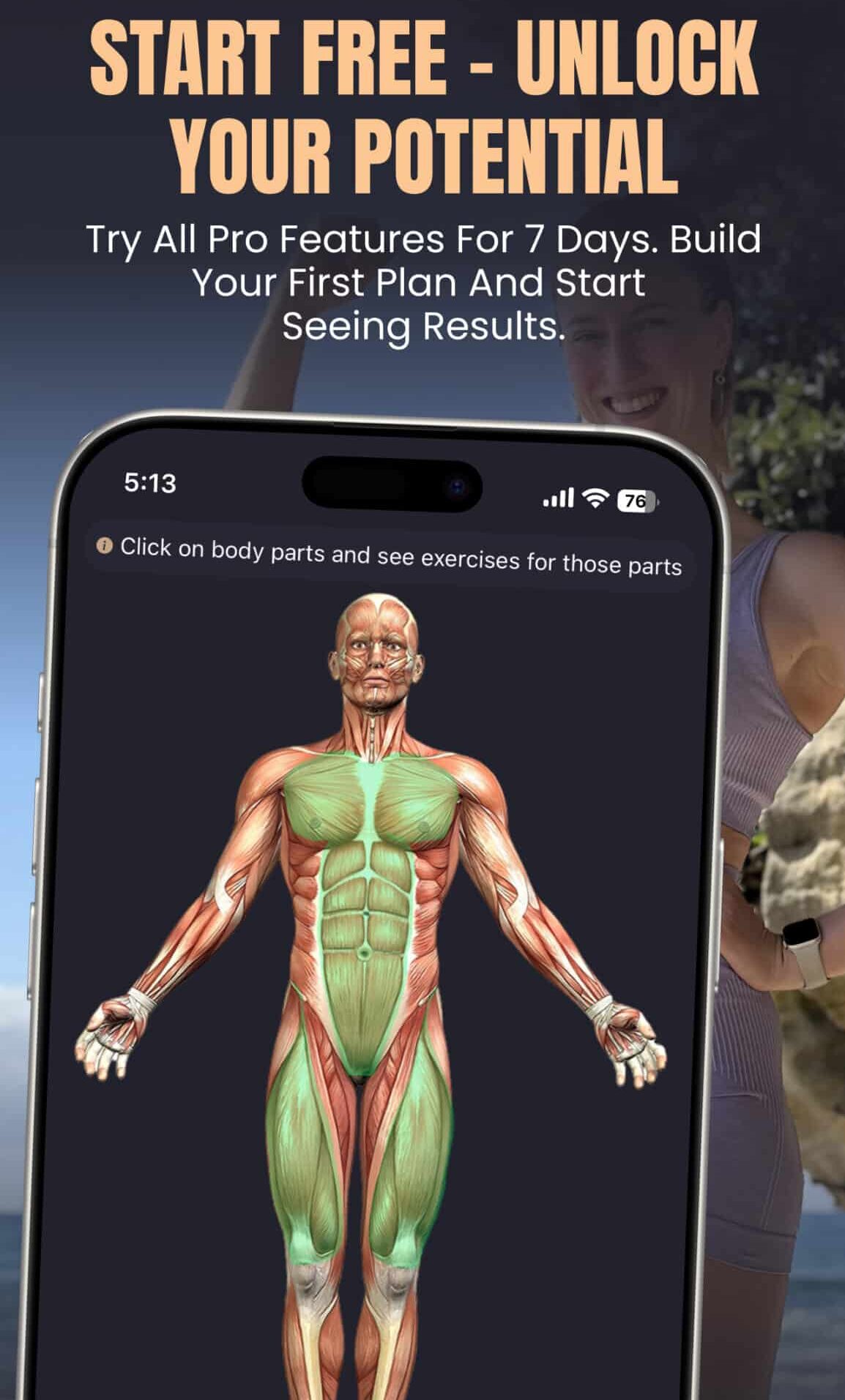

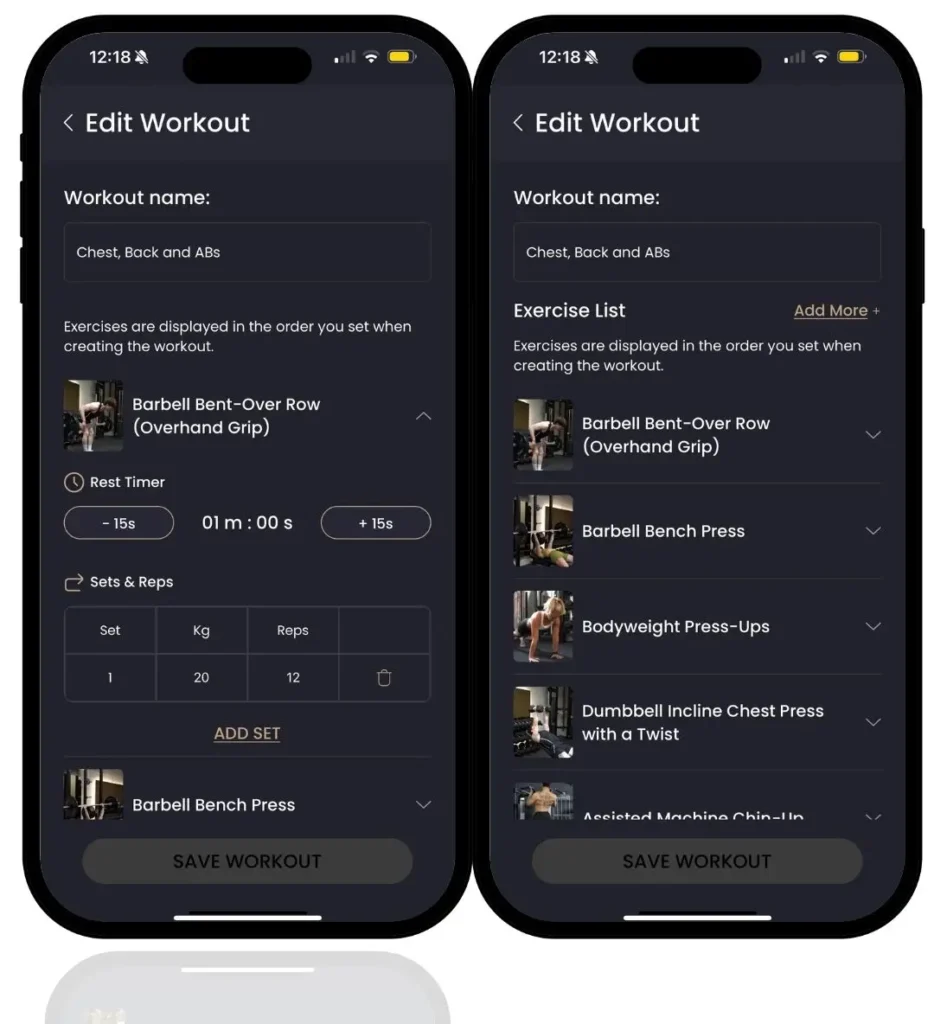

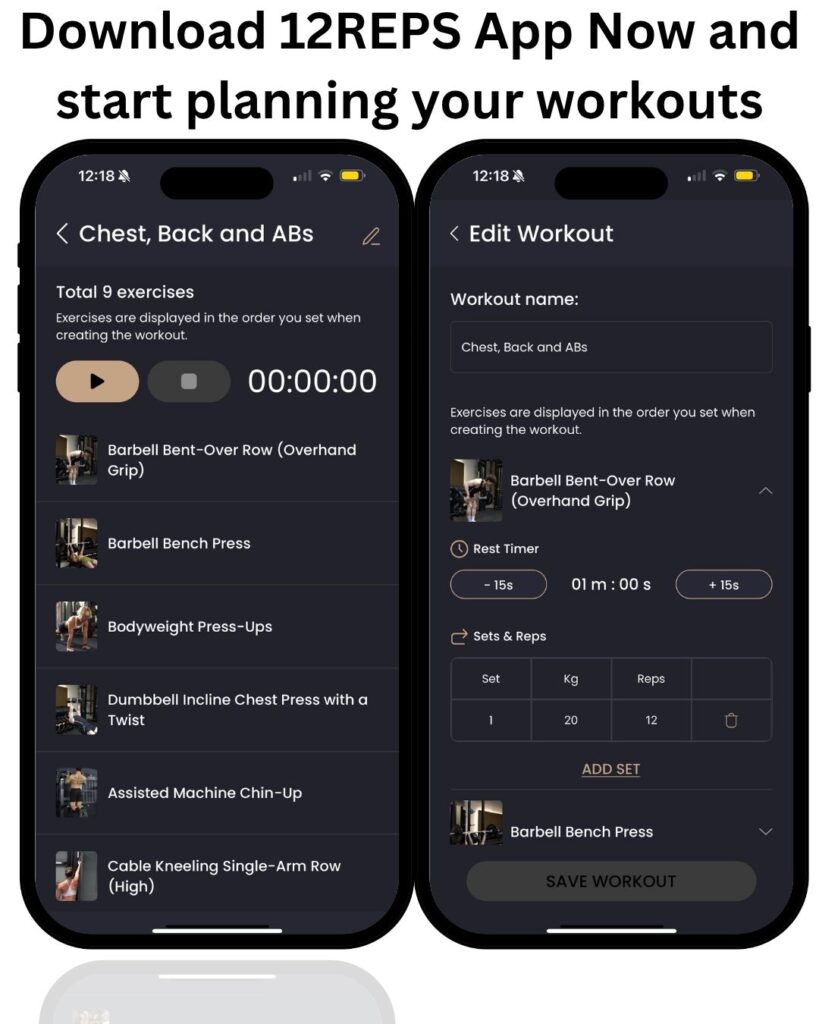

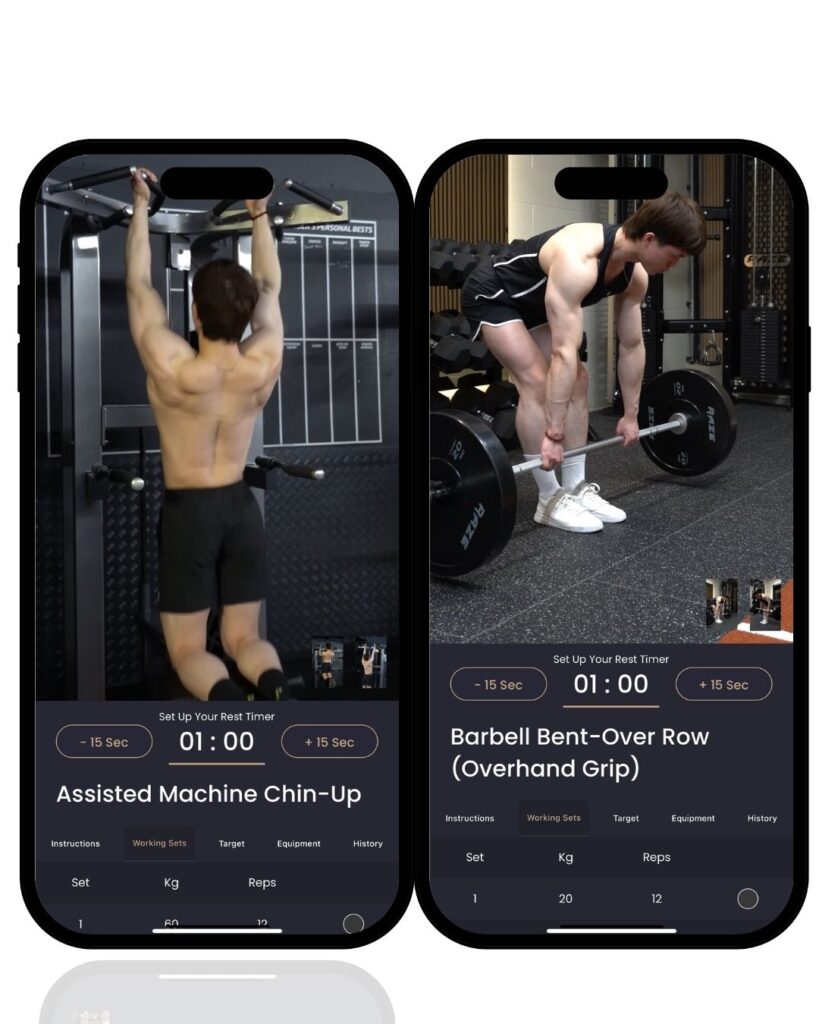

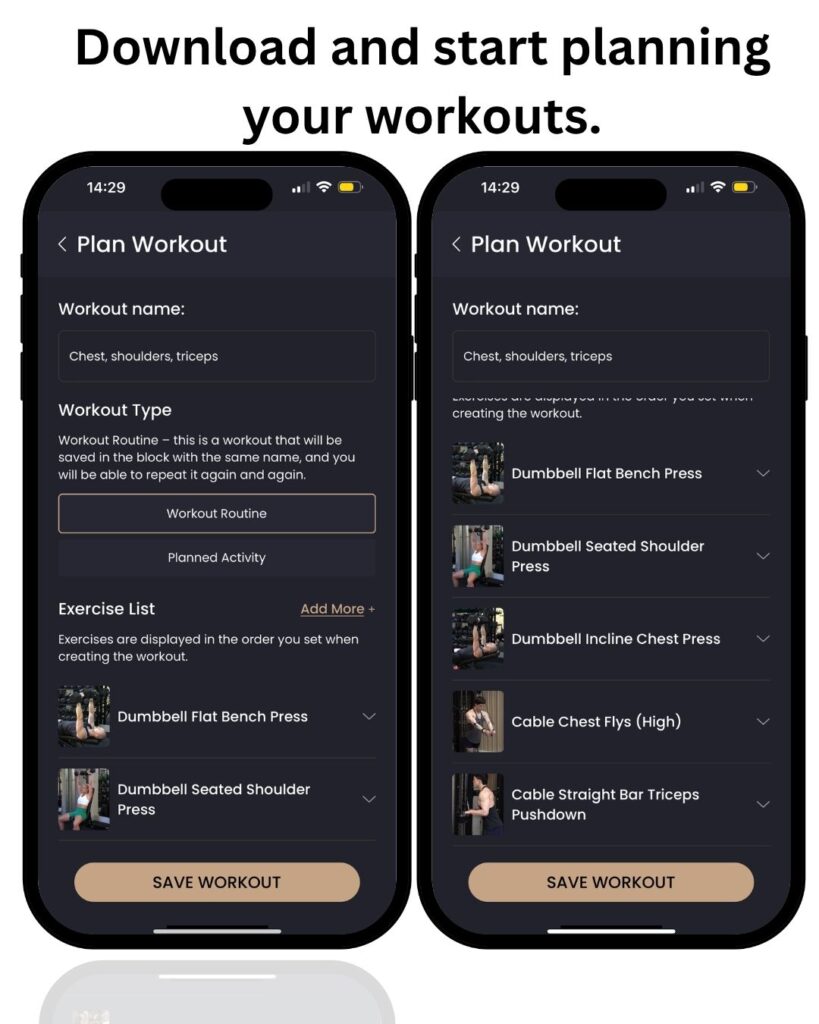

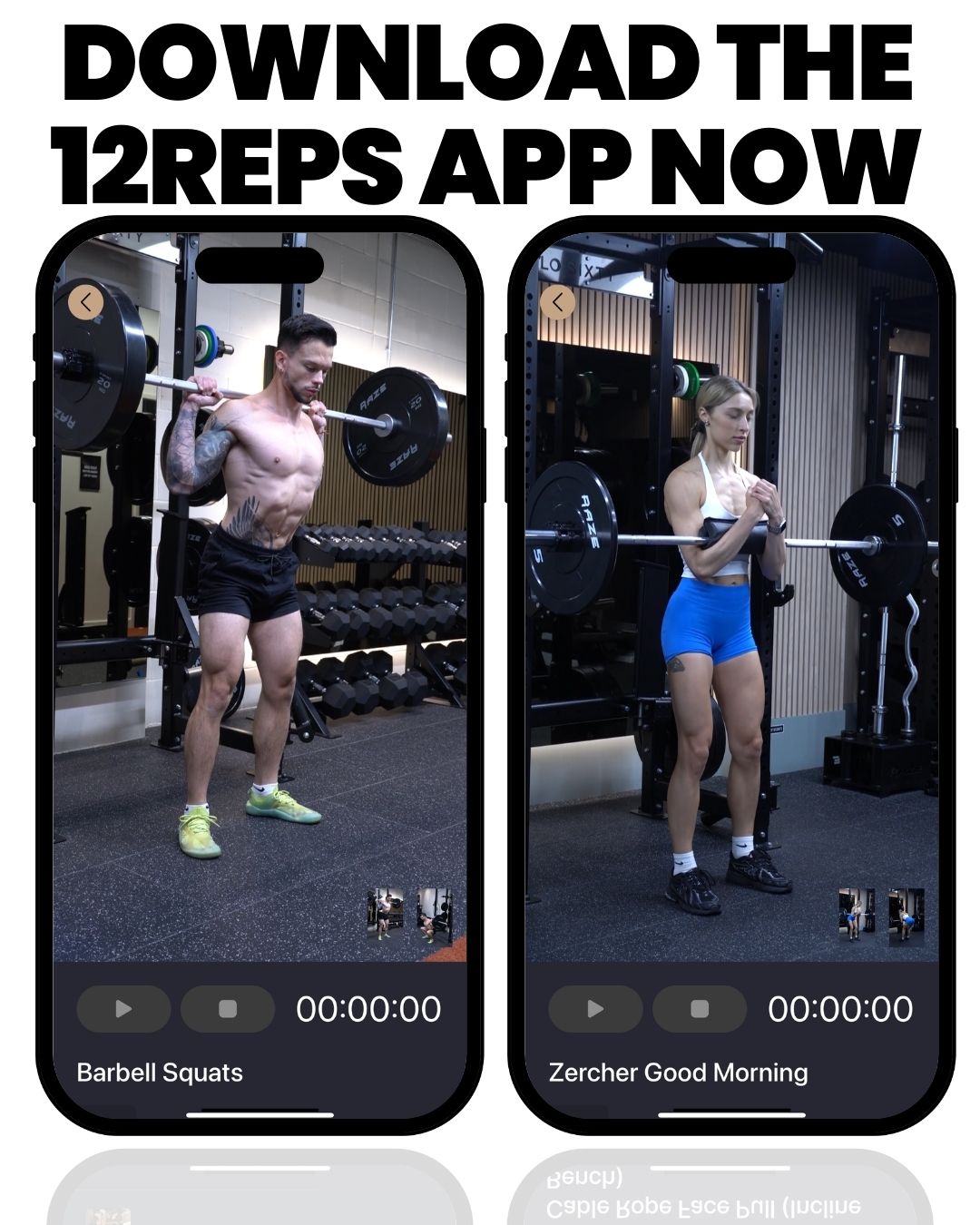

The progression strategy during Phase 1 focuses on movement quality and volume increases rather than external loading. Runners should master each movement pattern before advancing to more challenging variations. The bodyweight nature of this phase allows for daily practice of movement patterns, accelerating the learning process and building the foundation for subsequent phases. Download the 12reps app to see exercise demos.

Phase 2: Strength Development (Weeks 5-8) - Free Weights Introduction

Phase 2 marks the transition from bodyweight training to loaded exercises, introducing free weights systematically and progressively. This phase builds upon the movement foundations established in Phase 1, adding external resistance to develop absolute strength and muscular endurance. The introduction of free weights allows for precise load progression and targets the strength qualities most relevant to running performance.

The primary adaptations during Phase 2 are both neurological and structural. The nervous system continues to refine movement patterns whilst adapting to external loading, whilst muscle fibres begin to undergo the structural changes associated with strength development. This dual adaptation process is crucial for runners, as it develops strength without compromising the movement efficiency essential for distance running.

Deadlift training becomes a cornerstone of Phase 2, introducing one of the most functional movement patterns for runners. The Romanian deadlift variation used in this program specifically targets the posterior chain, glutes, hamstrings, and erector spinae, which are critical for running power and injury prevention. The hip hinge pattern developed through deadlift training directly transfers to improved running mechanics and reduced injury risk.

The loading parameters in Phase 2 are carefully calibrated to develop strength-endurance rather than pure strength or hypertrophy. The 12-15 rep range with moderate loads creates the optimal stimulus for the strength qualities that enhance running performance. This approach avoids the excessive muscle mass that could impair running economy whilst developing the force production capabilities that improve performance.

Phase 2 Workout Tables

Push Day – Phase 2

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Dumbbell Chest Press | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Increase weight weekly |

Overhead Press (dumbbells) | 1 x 8 light | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Focus on core stability |

Dumbbell Flyes | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Control the negative |

Close-grip Push-ups | 1 x 8 | 4 x 10-15 | 10-15 | 45s | Target triceps |

Lateral Raises | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Light weight, perfect form |

Pull Day – Phase 2

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Bent-over Dumbbell Rows | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Keep core tight |

Single-arm Dumbbell Rows | 1 x 8 each light | 4 x 12-15 each | 12-15 | 45s | Focus on lat engagement |

Reverse Flyes (dumbbells) | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Rear delt focus |

Bicep Curls | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Control the movement |

Face Pulls (resistance band) | 1 x 10 | 4 x 15-20 | 15-20 | 45s | External rotation focus |

Legs Day – Phase 2

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Goblet Squats | 1 x 10 light | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Hold dumbbell at chest |

Romanian Deadlifts | 1 x 8 light | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Focus on hip hinge |

Dumbbell Lunges | 1 x 6 each light | 4 x 12-15 each | 12-16 | 45s | Add weight gradually |

Single-leg Calf Raises | 1 x 10 each | 4 x 12-15 each | 12-16 | 45s | Hold dumbbell for load |

Farmer’s Walks | 1 x 20m light | 4 x 30-40m | 30-40m | 45s | Functional core strength |

The progression strategy in Phase 2 emphasises gradual load increases whilst maintaining movement quality. Runners should focus on perfect form with lighter weights before progressing to heavier loads. The introduction of unilateral exercises (single-arm rows, single-leg calf raises) addresses the asymmetries common in distance runners whilst developing the stability and coordination essential for efficient running mechanics.

The metabolic demands of Phase 2 increase significantly compared to Phase 1, developing the anaerobic capacity that complements aerobic training. The combination of moderate loads and short rest periods creates a training stimulus that enhances both strength and metabolic conditioning, preparing runners for the higher-intensity demands of Phase 3.

Download the 12reps app to see exercise demos

Phase 3: Power and Performance (Weeks 9-12) - Advanced Movements

Phase 3 represents the culmination of the 12-week program, focusing on power development and advanced movement patterns that directly enhance competitive running performance. This phase introduces explosive exercises and higher loads, developing the anaerobic power and neuromuscular qualities that separate competitive athletes from recreational runners. The emphasis shifts from building strength foundations to expressing that strength through powerful, dynamic movements.

The adaptations in Phase 3 are primarily neurological, focusing on rate of force development and intermuscular coordination. These qualities are crucial for Hyrox hybrid athlete performance, where rapid transitions between strength and endurance demands require exceptional neuromuscular efficiency. The explosive exercises in this phase develop the fast-twitch muscle fibres that contribute to running speed and the ability to respond to race dynamics.

Power development in Phase 3 occurs through multiple training methods. Plyometric exercises like jump squats develop reactive strength and elastic energy utilisation. Olympic lift variations like dumbbell thrusters train the ability to generate force rapidly through multiple joints. Heavy strength exercises with lower rep ranges develop maximal force production capabilities. This multi-faceted approach ensures comprehensive power development that transfers to running performance.

The integration of power training with endurance development creates the hybrid athlete profile that characterises modern competitive running. Hyrox training demands exactly this combination of qualities, the ability to maintain high power outputs across multiple modalities whilst recovering rapidly between efforts. Phase 3 develops these qualities through progressive overload and movement complexity.

Phase 3 Workout Tables

Push Day – Phase 3

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Dumbbell Bench Press | 1 x 10 moderate | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Heavier loads |

Push Press (dumbbells) | 1 x 8 light | 4 x 8-10 | 8-10 | 45s | Explosive movement |

Incline Dumbbell Press | 1 x 10 moderate | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Upper chest focus |

Dumbbell Thrusters | 1 x 8 light | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Full body power |

Plyo Push-ups | 1 x 5 | 3 x 6-10 | 6-10 | 45s | Explosive power |

Pull Day – Phase 3

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Weighted Pull-ups/Chin-ups | 1 x 5 bodyweight | 4 x 8-12 | 8-12 | 45s | Add weight if possible |

Renegade Rows | 1 x 6 light | 4 x 8-12 | 8-12 | 45s | Core and pull combined |

High Pulls (dumbbells) | 1 x 8 light | 4 x 8-10 | 8-10 | 45s | Explosive pulling |

Hammer Curls | 1 x 10 moderate | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Grip strength focus |

Band Pull-aparts | 1 x 15 | 4 x 15-20 | 15-20 | 45s | Rear delt activation |

Legs Day – Phase 3

Exercise | Warm-up Set | Working Sets | Reps | Rest | Progression Notes |

Dumbbell Squats | 1 x 10 moderate | 4 x 10-12 | 10-12 | 45s | Heavier loads |

Single-leg Deadlifts | 1 x 6 each light | 4 x 8-12 each | 8-12 | 45s | Balance and strength |

Jump Squats | 1 x 8 bodyweight | 4 x 8-12 | 8-12 | 45s | Explosive power |

Bulgarian Split Squats | 1 x 8 each light | 4 x 10-12 each | 10-12 | 45s | Single leg strength |

Weighted Calf Raises | 1 x 12 moderate | 4 x 12-15 | 12-15 | 45s | Heavy load focus |

The progression strategy in Phase 3 emphasises movement velocity and power output rather than simply increasing load. Runners should focus on explosive execution of concentric movements whilst maintaining control during eccentric phases. The introduction of plyometric exercises requires careful attention to landing mechanics and progressive volume increases to prevent injury.

The metabolic demands of Phase 3 peak during this program, creating training stimuli that closely mirror competitive demands. The combination of heavy loads, explosive movements, and short rest periods develops the anaerobic power and recovery capacity essential for competitive running performance. This phase prepares runners for the physiological demands of racing whilst building the confidence that comes from feeling truly strong and powerful.

Implementation Tips and Recovery Protocols

Successfully integrating this marathon strength training program with running training requires strategic planning and attention to recovery protocols. The key to success lies in viewing strength training as complementary to rather than competitive with running training. This mindset shift ensures that strength sessions enhance rather than compromise running performance.

The optimal scheduling places strength sessions on easy running days or as part of double sessions with easy runs. This approach allows for high-quality strength work whilst preserving energy for key running sessions. Leg sessions should be scheduled with particular care, ideally 48 hours before hard running sessions to allow for adequate recovery. The program’s three sessions per week frequency provides flexibility for integration with various running schedules.

Recovery protocols become increasingly crucial as the program progresses and training loads increase. Active recovery strategies such as light movement, stretching, and foam rolling should be incorporated daily. Sleep quality and duration directly impact adaptation to strength training, with 7-9 hours of quality sleep being essential for optimal recovery. Nutrition timing around strength sessions should emphasise protein intake within 2 hours post-exercise to support muscle protein synthesis.

The 12reps app and similar training platforms can be valuable tools for tracking progress and ensuring consistent progression throughout the program. Digital tracking allows for precise load management and helps identify patterns in performance and recovery. However, technology should supplement rather than replace attention to subjective markers of recovery such as energy levels, motivation, and movement quality.

Adaptation to strength training occurs during recovery periods rather than during training sessions themselves. This principle is particularly important for runners, who often struggle with the concept of planned recovery. The program’s built-in progression ensures that training loads increase systematically, but individual responses may vary. Runners should be prepared to adjust loads or extend phases based on their individual recovery capacity.

Common implementation mistakes include progressing too quickly through phases, neglecting movement quality in favour of heavier loads, and failing to integrate strength training with running periodisation. The conservative progression built into this program helps prevent these errors, but individual responsibility for movement quality and load management remains crucial.

Conclusion

This 12-week push/pull/legs program represents a comprehensive approach to athletic strength training that addresses the specific needs of distance runners. Through systematic progression from bodyweight foundations to advanced power development, the program builds the strength qualities that enhance running performance whilst reducing injury risk.

The integration of multiple energy systems, functional movement patterns, and progressive overload creates adaptations that extend far beyond simple strength gains. Runners who complete this program will experience improved running economy, enhanced anaerobic capacity, better body composition, and the confidence that comes from feeling truly strong and resilient.

Whether you’re preparing for your first marathon, training for Hyrox training competitions, or simply seeking to become a more complete athlete, this program provides the foundation for long-term success. The principles and progressions outlined here can be adapted and repeated throughout your athletic career, ensuring continued development and injury prevention.

As an experienced strength and conditioning coach, I’ve seen countless runners transform their performance through systematic strength training. The program outlined here represents the distillation of years of experience working with athletes at all levels. Trust the process, focus on movement quality, and prepare to discover what you’re truly capable of achieving.

Remember, strength training isn’t just about becoming a better runner, it’s about becoming a more resilient, capable, and confident athlete in all aspects of life. The strength you build in the gym will serve you not just in races, but in every physical challenge you encounter.

References

[1] Blagrove, R. C., Howatson, G., & Hayes, P. R. (2018). Effects of strength training on the physiological determinants of middle-and long-distance running performance: a systematic review. Sports Medicine, 48(5), 1117-1149. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-017-0835-7

[2] Cavanagh, P. R., & Lafortune, M. A. (1980). Ground reaction forces in distance running. Journal of Biomechanics, 13(5), 397-406.

[3] Yamamoto, L. M., Lopez, R. M., Klau, J. F., Casa, D. J., Kraemer, W. J., & Maresh, C. M. (2008). The effects of resistance training on endurance distance running performance among highly trained runners: a systematic review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(6), 2036-2044. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2008/11000/the_effects_of_resistance_training_on_endurance.43.aspx

[4] Jung, A. P. (2003). The impact of resistance training on distance running performance. Sports Medicine, 33(7), 539-552. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00007256-200333070-00005

[5] Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871-877.

[6] Brandt, T., Ebel, C., Lebahn, C., & Schmidt, A. (2025). Acute physiological responses and performance determinants in Hyrox© – a new running-focused high intensity functional fitness trend. Frontiers in Physiology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1519240/full

[7] Roelofs, E. J., Smith-Ryan, A. E., Melvin, M. N., Wingfield, H. L., Trexler, E. T., & Walker, N. (2015). Muscle size, quality, and body composition: characteristics of division I cross-country runners. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(2), 290-296. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/FullText/2015/02000/Muscle_Size,_Quality,_and_Body_Composition_.2.aspx

[8] Aloia, J. F., Cohn, S. H., Babu, T., Abesamis, C., Kalici, N., & Ellis, K. (1978). Skeletal mass and body composition in marathon runners. Metabolism, 27(12), 1793-1796. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0026049578902652

[9] Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance training is medicine: effects of strength training on health. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209-216.

[10] Kraemer, W. J., & Ratamess, N. A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 35(4), 339-361.

[11] Mikkola, J. S., Rusko, H. K., Nummela, A. T., Pollari, T., & Häkkinen, K. (2007). Concurrent endurance and explosive type strength training increases activation and fast force production of leg extensor muscles in endurance athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(2), 613-620. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/abstract/2007/05000/concurrent_endurance_and_explosive_type_strength.56.aspx

[12] Brooks, G. A., & Mercier, J. (1994). Balance of carbohydrate and lipid utilization during exercise: the “crossover” concept. Journal of Applied Physiology, 76(6), 2253-2261.

[13] Heinonen, A., Oja, P., Kannus, P., Sievänen, H., Mänttäri, A., & Vuori, I. (1993). Bone mineral density of female athletes in different sports. Bone and Mineral, 23(1), 1-14.